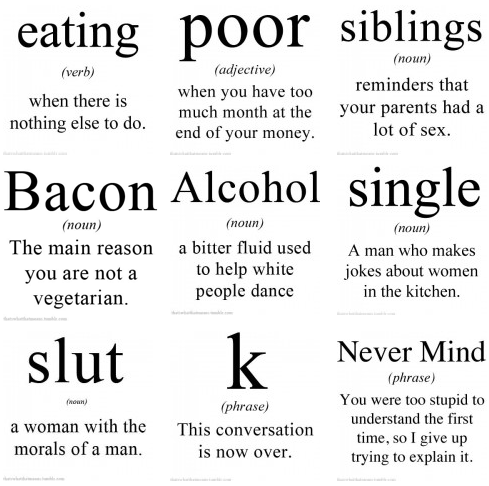

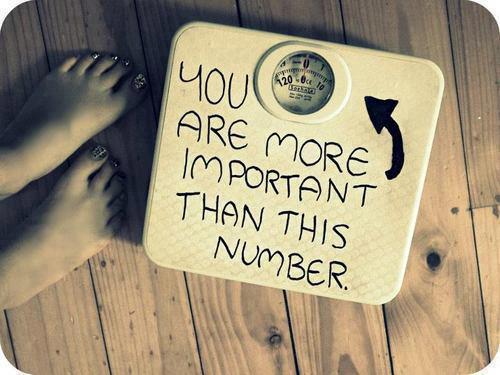

Funny Love Saying Definition

Source(Google.com.pk)

The most elaborate description of romantic love is found in Stendhal's Love (1975). Although he denies that passionate love is pathological, he inconsistently acknowledges that it is a disease. Certainly his description emphasizes the painful rather than the pleasurable aspects. At the beginning, one is lost in obsession:

The most surprising thing of all about love is the first step, the violence of the change that takes place in the mind… A person in love in unremittingly and uninterruptedly occupied with the image of the beloved.

In the later stages, Stendahl notes, many other surprises await, most of them unpleasant: "Then you reach the final torment: utter despair poisoned still further by a shred of hope"

Although Stendahl included positive aspects of love, the philosopher Ortega y Gasset saw only the negative (On Love 1957), calling romantic love an abnormality. This passage suggests the flavor of his critique:

The soul of a man in love smells of the closed-up room of a sick man--its confined atmosphere is filled with stale breath.

Even Freud, a champion of sexuality, saw romantic love negatively. He commented that falling in love was a kind of "sickness and craziness, an illusion, a blindness to what the loved person is really like" (Freud 1915). Here he seems to equate love with infatuation, a topic I will take up below.

On the other hand, to give Freud credit, he also saw the positive side of love, at least of non-erotic love. When Jung challenged him to name the curative aspect of psychoanalysis, Freud answered very simply “Love.” This answer is very much in harmony with the definition of love that will be offered in this chapter.

Modern scholarship is more evenly divided between positive and negative views than classical discussions. Hatfield and Rapson (1993) distinguish between passionate love (infatuation) and companionate love (fondness). Both Solomon (1992) and Sternberg (1988) distinguish between love and infatuation. They note that both involve intense desire, but that love also involves intimacy and commitment. Kemper and Reid (1997) also distinguish between what they call “adulation” and what they see as later stages, ideal and romantic love. Like Persons (1988), they seem to assume that beginning with infatuation is likely to lead on to love.

In my experience, infatuation mostly leads to more infatuation, either with the same or different persons. For Solomon and for Sternberg, love is highly positive and complex; it is infatuation that is simple and negative. As we shall see, this distinction may be too crude. But, if refined, it could be a step toward the development of a workable concept of love.

A very detailed and precise analysis of the meaning of the word love in English is provided by Johnson (2001). He shows that the vernacular word implies three different kinds of love: care, desire for union, or appreciation. These three forms, he argues, may exist independently or in combination. One limitation of his approach is that it does not include the physical component of love, attachment. Another is that it is atheoretical, in that it is based entirely on vernacular usage in the English language. Although it is useful to have such a detailed treatment, it still leaves the analysis of the meaning of love located completely in only one culture.

Kemper (1978) analyzed the way in which social relationships generate love as well as other emotions, in terms of status and power. The awarding of status, which is crucial in Kemper’s theory, will be important here also, since it is an aspect of shared identity. Power, however, does not seem to be involved in love as defined here, since shared identity means its absence. Although I agree that most emotions arise out of relationship dynamics, Kemper’s theory seems to deal only partially with shared identity, and not at all with attachment, attraction, and empathic resonance (attunement).

Perhaps the best empirical study of romantic love, and certainly the most detailed, is by Tennov (1979), who interviewed hundreds of persons about their romantic life. She found that the great majority of her subjects had frequently experienced the trance of love, like the one in Sappho's poem. However, Tennov does not call this state love or even infatuation. Instead she used the word “limerance,” which refers to a trance-like state. Perhaps aware of the many ambiguities in the way the word love is used, Tennov seems to have wanted a neutral term, rather than the usual one.

The conflict between the different points of view described above is the result, for the most part, of the broad sweep covered by the word love. The argument is a confusion of meanings, since the various sides are referring to different affects. Those who see romantic love as pathological are considering the affect that I prefer to call infatuation and/or the sex drive, without considering other aspects of what is called love. This usage is perfectly proper in English and French (but not in Spanish). Most references to “falling in love” or “love at first sight” concern infatuation. And with regard to lust, recall that one of the dictionary definitions of love is “A feeling of intense desire and attraction toward a person with whom one is disposed to make a pair; the emotion of sex and romance,” which is entirely about sexual desire.

On the other hand, those authors that stress the positive aspects of love focus on the emotional and relational aspects, companionship and caring. I will consider these aspects under the heading of “attunement,” the sharing of identity and awareness between persons in love. As should become clear in this essay, this is only one part of love, even non-erotic love. Perhaps there will be less conflict and confusion if we can agree on a definition of love that is less vague and broad than vernacular usage.

Two Components of Love

The social science literature on love is divided into two separate schools of thought. The first school focuses on biology. This school holds that attachment, a genetically endowed physical phenomenon is the basis for non-erotic love, and that sexual attraction, together with attachment, are the twin bases of erotic love. The idea that the dominant force in love is attachment and/or sexual attraction is stated explicitly by Shaver (1994), Shackleford (1998), Fisher (1992), and many others. This idea has strong connections with evolutionary theory, proposing that love is a mammalian drive, like hunger and thirst.

The most surprising thing of all about love is the first step, the violence of the change that takes place in the mind… A person in love in unremittingly and uninterruptedly occupied with the image of the beloved.

In the later stages, Stendahl notes, many other surprises await, most of them unpleasant: "Then you reach the final torment: utter despair poisoned still further by a shred of hope"

Although Stendahl included positive aspects of love, the philosopher Ortega y Gasset saw only the negative (On Love 1957), calling romantic love an abnormality. This passage suggests the flavor of his critique:

The soul of a man in love smells of the closed-up room of a sick man--its confined atmosphere is filled with stale breath.

Even Freud, a champion of sexuality, saw romantic love negatively. He commented that falling in love was a kind of "sickness and craziness, an illusion, a blindness to what the loved person is really like" (Freud 1915). Here he seems to equate love with infatuation, a topic I will take up below.

On the other hand, to give Freud credit, he also saw the positive side of love, at least of non-erotic love. When Jung challenged him to name the curative aspect of psychoanalysis, Freud answered very simply “Love.” This answer is very much in harmony with the definition of love that will be offered in this chapter.

Modern scholarship is more evenly divided between positive and negative views than classical discussions. Hatfield and Rapson (1993) distinguish between passionate love (infatuation) and companionate love (fondness). Both Solomon (1992) and Sternberg (1988) distinguish between love and infatuation. They note that both involve intense desire, but that love also involves intimacy and commitment. Kemper and Reid (1997) also distinguish between what they call “adulation” and what they see as later stages, ideal and romantic love. Like Persons (1988), they seem to assume that beginning with infatuation is likely to lead on to love.

In my experience, infatuation mostly leads to more infatuation, either with the same or different persons. For Solomon and for Sternberg, love is highly positive and complex; it is infatuation that is simple and negative. As we shall see, this distinction may be too crude. But, if refined, it could be a step toward the development of a workable concept of love.

A very detailed and precise analysis of the meaning of the word love in English is provided by Johnson (2001). He shows that the vernacular word implies three different kinds of love: care, desire for union, or appreciation. These three forms, he argues, may exist independently or in combination. One limitation of his approach is that it does not include the physical component of love, attachment. Another is that it is atheoretical, in that it is based entirely on vernacular usage in the English language. Although it is useful to have such a detailed treatment, it still leaves the analysis of the meaning of love located completely in only one culture.

Kemper (1978) analyzed the way in which social relationships generate love as well as other emotions, in terms of status and power. The awarding of status, which is crucial in Kemper’s theory, will be important here also, since it is an aspect of shared identity. Power, however, does not seem to be involved in love as defined here, since shared identity means its absence. Although I agree that most emotions arise out of relationship dynamics, Kemper’s theory seems to deal only partially with shared identity, and not at all with attachment, attraction, and empathic resonance (attunement).

Perhaps the best empirical study of romantic love, and certainly the most detailed, is by Tennov (1979), who interviewed hundreds of persons about their romantic life. She found that the great majority of her subjects had frequently experienced the trance of love, like the one in Sappho's poem. However, Tennov does not call this state love or even infatuation. Instead she used the word “limerance,” which refers to a trance-like state. Perhaps aware of the many ambiguities in the way the word love is used, Tennov seems to have wanted a neutral term, rather than the usual one.

The conflict between the different points of view described above is the result, for the most part, of the broad sweep covered by the word love. The argument is a confusion of meanings, since the various sides are referring to different affects. Those who see romantic love as pathological are considering the affect that I prefer to call infatuation and/or the sex drive, without considering other aspects of what is called love. This usage is perfectly proper in English and French (but not in Spanish). Most references to “falling in love” or “love at first sight” concern infatuation. And with regard to lust, recall that one of the dictionary definitions of love is “A feeling of intense desire and attraction toward a person with whom one is disposed to make a pair; the emotion of sex and romance,” which is entirely about sexual desire.

On the other hand, those authors that stress the positive aspects of love focus on the emotional and relational aspects, companionship and caring. I will consider these aspects under the heading of “attunement,” the sharing of identity and awareness between persons in love. As should become clear in this essay, this is only one part of love, even non-erotic love. Perhaps there will be less conflict and confusion if we can agree on a definition of love that is less vague and broad than vernacular usage.

Two Components of Love

The social science literature on love is divided into two separate schools of thought. The first school focuses on biology. This school holds that attachment, a genetically endowed physical phenomenon is the basis for non-erotic love, and that sexual attraction, together with attachment, are the twin bases of erotic love. The idea that the dominant force in love is attachment and/or sexual attraction is stated explicitly by Shaver (1994), Shackleford (1998), Fisher (1992), and many others. This idea has strong connections with evolutionary theory, proposing that love is a mammalian drive, like hunger and thirst.

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Saying Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment