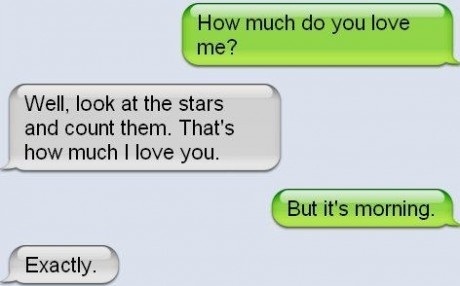

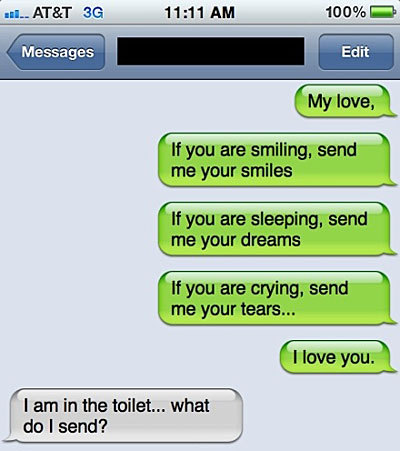

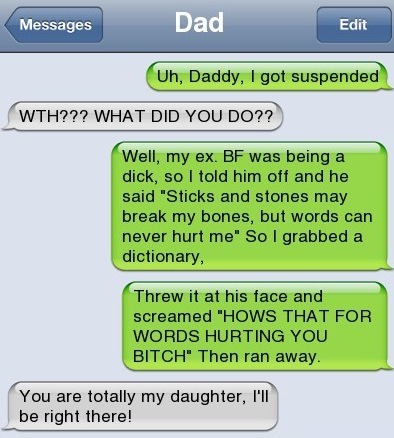

Funny Love Texts Definition

Source(Google.com.pk)

There are many features of Solomon’s treatment of love that distinguish it from other writings. First, his analysis of love is conceptual and comparative: in his treatments, he examines love in the context of a similar examination of other emotions. The way in which he compared the broadness of the meaning of love with the narrowness of other emotions, quoted above, is illustrative of his approach. Indeed, his first analysis of love occurred in a volume in which he gave more or less equal space to the other major emotions (The Passions 1976). Locating love with respect to other emotions is extremely important, since many of the classical and modern discussions get lost in the uniqueness, and therefore the ineffability of love.

A second feature of his approach is that he provides a broad picture of the effects of emotion on the person undergoing them, in addition to the central feeling. He calls this broad summary “the emotionworld.” For example, he compares the “loveworld” to the “angerworld.” The loveworld (Solomon 1981, p. 126) is “woven around a single relationship, with everything else pushed to the periphery...” By contrast, he states, in the angerworld “one defines oneself in the role the ‘the offended’ and someone else….as the ‘offender. [It] is very much a courtroom world, a world filled with blame and emotional litigation...” Solomon uses the skills of a novelist to try to convey the experience of emotion, including cognition and perception, not just the sensation or the outward appearance.

From my point of view, however, Solomon’s most significant stroke involves his definition of the central feature of love as shared identity (Solomon 1981, p.xxx; 1994, p.235): “ …love [is] shared identity, a redefinition of self which no amount of sex or fun or time together will add up to….Two people in a society with an extraordinary sense of individual identity mutually fantasize, verbalize and act their way into a relationship that can no longer be understood as a mere conjunction of the two but only as a complex ONE. “

By locating love in the larger perceptual/behavioral framework, and by comparing love with other emotions, Solomon manages both to evoke love as an emotion, and develop a concrete description of its causes, appearance and effects, a significant achievement. His work suggests that the reason scholars decide that love is ineffable is because they treat it that way, a self-fulfilling prophecy that Solomon avoids.

At first sight, Solomon’s deconstruction of the concept of love may appear to be Grinch-like. Why remove the aura of ineffability, of sacred mystery by means of comparison with other emotions, by locating feelings within a larger framework of perceptions and behavior, and by invoking a general concept like shared identity? Perhaps this attempt is only one more example of what Max Weber called the progressive disenchantment of the world.

This is an important issue; we cannot afford just to shrug it off. Perhaps it is the price one has to pay for the advancement of understanding. But there us a further reason that is less obvious. One implication of Chapter 2 is that the broad use of the word love is a defense against painful feelings of separation and alienation. It is possible that the way that the idea of love evokes positive feelings of awe and mystery is also a defense against painful feelings of separation and alienation.

In any event, this chapter seeks to extend Solomon’s conceptualization of love as an emotion like other emotions. Solomon’s idea that genuine love involves a union between the lovers is not new. It is found, as he suggests, in Plato and Aristotle. It also appears in one of Shakespeare’s riddling poems about love, The Phoenix and the Turtle, as in this stanza: The idea of unity is also alluded to in the first dictionary definition, quoted above, as “a sense of oneness,” and in many other conceptions of the nature of love. In current discussion, the idea of unity is referred to as connectedness, shared awareness, intersubjectivity, or attunement.

In order to develop a usable definition of love, I will draw upon both literatures, the one on attachment, the other on attunement. For romantic love, a third “A” is needed, (sexual) attraction. Any theory of social integration, like attachment theory, assumes that humanness requires being connected to others. There is a vast literature supporting the idea that all humans have a need to belong (Baumeister and Leary 1995). Love is one form of belonging, friendship and community are two other forms. But in modern societies these kinds of needs are difficult to fulfil. Infatuation, heartbreak, and on a larger scale, blind patriotism offer a substitute: imagining and longing for an ideal person or group instead of connecting with a real one.

One complication involved with the idea of the need for connectedness is that humans, unlike other mammals, also have a strong need for individual and group autonomy. These two needs are equal and opposite. The clash between needs for both connection and autonomy form the backdrop for cooperation and conflict between individuals and groups. I will return to the issue of autonomy in the discussion of micro-solidarity and micro-alienation below.

The idea of a connection between two persons is difficult to make explicit in Western societies because of the strong focus on individuals, rather than relationships. It implies that humans, unlike other creatures, can share the experience of another. That is, that a part of individual consciousness is not only subjective, but also intersubjective.

The idea of an intersubjective component in consciousness has been mentioned many times in the history of philosophy, but the implications are seldom explored. As indicated in Chapter 2, Cooley argued that intersubjectivity is so much a part of the humanness of human nature that most of us take it completely for granted, to the point of invisibility:

The idea that we “[live} in the minds of others without knowing it” is profoundly significant for understanding the cognitive component of love. Intersubjectivity is so built into our humanness that it will usually be virtually invisible. It follows that we should expect that not only laypersons but most social scientists avoid explicit consideration of intersubjectivity.

This element is what Stern (1977) has called attunement (mutual understanding). John Dewey proposed that attunement formed the core of communication:

Shared experience is the greatest of human goods. In communication, such conjunction and contact as is characteristic of animals become endearments capable of infinite idealization; they become symbols of the very culmination of nature (Dewey 1925, p.202)

In ordinary language, attunement involves connectedness between people, deep and seemingly effortless understanding, and understanding that one is understood. As already indicated, this idea is hinted at in that part of the dictionary definition about "a sense of oneness."

In order to visualize intersubjectivity, it may be necessary to take this idea a step further than Cooley did, by thinking of it more concretely. How does it actually work in dialogue? One recent suggestion that may be helpful is the idea of “pendulation,” that interacting with others, we swing back and forth between our own point of view, and that of the other (Levine 1997). It is this back and forth movement between subjective and intersubjective consciousness that allows mutual understanding.

The infinite ambiguity of ordinary human language makes intersubjectivity (shared consciousness) a necessity for communication. The signs and gestures used by non-human creatures are virtually without ambiguity. In the world of bees, the smell of bees from outside the nest is clearly different than the smell of one’s own nest: it signals enemy. But humans can easily hide their feelings and intentions under deceitful or ambiguous messages. Even with the best intentions, communications in ordinary language are inherently ambiguous, because all ordinary words are allowed many meanings, depending on the context. Understanding even fairly simple messages requires mutual role-taking (attunement) because the meaning of messages is dependent on the context.

A second feature of his approach is that he provides a broad picture of the effects of emotion on the person undergoing them, in addition to the central feeling. He calls this broad summary “the emotionworld.” For example, he compares the “loveworld” to the “angerworld.” The loveworld (Solomon 1981, p. 126) is “woven around a single relationship, with everything else pushed to the periphery...” By contrast, he states, in the angerworld “one defines oneself in the role the ‘the offended’ and someone else….as the ‘offender. [It] is very much a courtroom world, a world filled with blame and emotional litigation...” Solomon uses the skills of a novelist to try to convey the experience of emotion, including cognition and perception, not just the sensation or the outward appearance.

From my point of view, however, Solomon’s most significant stroke involves his definition of the central feature of love as shared identity (Solomon 1981, p.xxx; 1994, p.235): “ …love [is] shared identity, a redefinition of self which no amount of sex or fun or time together will add up to….Two people in a society with an extraordinary sense of individual identity mutually fantasize, verbalize and act their way into a relationship that can no longer be understood as a mere conjunction of the two but only as a complex ONE. “

By locating love in the larger perceptual/behavioral framework, and by comparing love with other emotions, Solomon manages both to evoke love as an emotion, and develop a concrete description of its causes, appearance and effects, a significant achievement. His work suggests that the reason scholars decide that love is ineffable is because they treat it that way, a self-fulfilling prophecy that Solomon avoids.

At first sight, Solomon’s deconstruction of the concept of love may appear to be Grinch-like. Why remove the aura of ineffability, of sacred mystery by means of comparison with other emotions, by locating feelings within a larger framework of perceptions and behavior, and by invoking a general concept like shared identity? Perhaps this attempt is only one more example of what Max Weber called the progressive disenchantment of the world.

This is an important issue; we cannot afford just to shrug it off. Perhaps it is the price one has to pay for the advancement of understanding. But there us a further reason that is less obvious. One implication of Chapter 2 is that the broad use of the word love is a defense against painful feelings of separation and alienation. It is possible that the way that the idea of love evokes positive feelings of awe and mystery is also a defense against painful feelings of separation and alienation.

In any event, this chapter seeks to extend Solomon’s conceptualization of love as an emotion like other emotions. Solomon’s idea that genuine love involves a union between the lovers is not new. It is found, as he suggests, in Plato and Aristotle. It also appears in one of Shakespeare’s riddling poems about love, The Phoenix and the Turtle, as in this stanza: The idea of unity is also alluded to in the first dictionary definition, quoted above, as “a sense of oneness,” and in many other conceptions of the nature of love. In current discussion, the idea of unity is referred to as connectedness, shared awareness, intersubjectivity, or attunement.

In order to develop a usable definition of love, I will draw upon both literatures, the one on attachment, the other on attunement. For romantic love, a third “A” is needed, (sexual) attraction. Any theory of social integration, like attachment theory, assumes that humanness requires being connected to others. There is a vast literature supporting the idea that all humans have a need to belong (Baumeister and Leary 1995). Love is one form of belonging, friendship and community are two other forms. But in modern societies these kinds of needs are difficult to fulfil. Infatuation, heartbreak, and on a larger scale, blind patriotism offer a substitute: imagining and longing for an ideal person or group instead of connecting with a real one.

One complication involved with the idea of the need for connectedness is that humans, unlike other mammals, also have a strong need for individual and group autonomy. These two needs are equal and opposite. The clash between needs for both connection and autonomy form the backdrop for cooperation and conflict between individuals and groups. I will return to the issue of autonomy in the discussion of micro-solidarity and micro-alienation below.

The idea of a connection between two persons is difficult to make explicit in Western societies because of the strong focus on individuals, rather than relationships. It implies that humans, unlike other creatures, can share the experience of another. That is, that a part of individual consciousness is not only subjective, but also intersubjective.

The idea of an intersubjective component in consciousness has been mentioned many times in the history of philosophy, but the implications are seldom explored. As indicated in Chapter 2, Cooley argued that intersubjectivity is so much a part of the humanness of human nature that most of us take it completely for granted, to the point of invisibility:

The idea that we “[live} in the minds of others without knowing it” is profoundly significant for understanding the cognitive component of love. Intersubjectivity is so built into our humanness that it will usually be virtually invisible. It follows that we should expect that not only laypersons but most social scientists avoid explicit consideration of intersubjectivity.

This element is what Stern (1977) has called attunement (mutual understanding). John Dewey proposed that attunement formed the core of communication:

Shared experience is the greatest of human goods. In communication, such conjunction and contact as is characteristic of animals become endearments capable of infinite idealization; they become symbols of the very culmination of nature (Dewey 1925, p.202)

In ordinary language, attunement involves connectedness between people, deep and seemingly effortless understanding, and understanding that one is understood. As already indicated, this idea is hinted at in that part of the dictionary definition about "a sense of oneness."

In order to visualize intersubjectivity, it may be necessary to take this idea a step further than Cooley did, by thinking of it more concretely. How does it actually work in dialogue? One recent suggestion that may be helpful is the idea of “pendulation,” that interacting with others, we swing back and forth between our own point of view, and that of the other (Levine 1997). It is this back and forth movement between subjective and intersubjective consciousness that allows mutual understanding.

The infinite ambiguity of ordinary human language makes intersubjectivity (shared consciousness) a necessity for communication. The signs and gestures used by non-human creatures are virtually without ambiguity. In the world of bees, the smell of bees from outside the nest is clearly different than the smell of one’s own nest: it signals enemy. But humans can easily hide their feelings and intentions under deceitful or ambiguous messages. Even with the best intentions, communications in ordinary language are inherently ambiguous, because all ordinary words are allowed many meanings, depending on the context. Understanding even fairly simple messages requires mutual role-taking (attunement) because the meaning of messages is dependent on the context.

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

Funny Love Texts Photos Pictures Pics Images 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment